|

English Language

|

Why are languages different?

What influences are at work to unify – and to divide – languages?

This is part of language change (see side panel). The basic question of "why does one group speak one language and the next speak another" has many answers.

The main influences:

Dividing:

- Time – speakers grow old and die, young speakers use the language to reflect their different attitudes and discoveries and so language change takes place.

- Geography and travel – seas and mountains separate groups of speakers so there is less contact. In time their languages drift apart, changing under different influences. Modern global travel and communications mitigate this.

Unifying:

- Government and laws – a sense of nationalism can guide or even enforce a particular form of language, though anti-nationalism may consolidate dialects or even separate language.

- Social and Tribal groups – the groups we mix with, the culture and history that we share, lead to a coalescence of language and common heritage. In time we will speak the same language as the people we like and understand and we may fear or be suspicious of those whose language is different

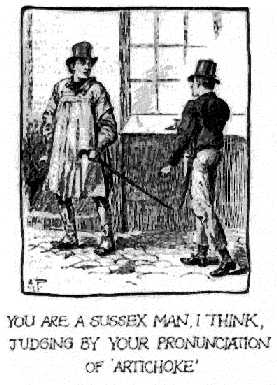

Idiolects and Dialects

Each of us speaks a variety of language that is unique to us. We are influenced by our parents, friends, experiences, religion etc so that everything in our lives has an effect on our choice of words and expression. This is our idiolect, our own personal language. An ideolect is a smaller language group than a dialect which in turn is smaller than a language. Each is a subset of the next.

These idiosyncrasies of our personal language are unlikely to be enough to cause problems with understanding by other members of our language group. Dialects (regional speech) may make it difficult, though not impossible, for different dialect groups to understand each other. Users of different languages will by definition be unable to understand each other. This is the criterion of “mutual incomprehensibility” which defines the difference between one language and another. And it is that principle of mutual incomprehensibility that is at work to ensure that a defined group can understand its members. If you can’t be understood you become part of another group, unable to share in the activities of the first group.

Variation

Imagine a linear continuum where each ideolect varies from the next by only 1%. Though each individual shares 99% of language and varies by only a small amount, the differences between idiolects at the ends of the continuum could be considerable. In principle this could lead to mutual incomprehensibility. In practice, in a country such as the UK the linear continuum effect is slight (though it accounts for the significant differences between Scots and Cornish accents and dialects) and the effect is more akin to overlapping pools than lines. Each pool has a number of linguistic features it shares with adjacent pools but the combination of features makes that area unique.

For example we may identify these pools as dialect areas popularly known as Geordie, Scouse, Brummy etc but in fact they are much more difficult to pin down as the large imprecise pools contain smaller pools until ultimately there are individual idiolects. So Geordie may be a convenient label for distant southerners to use of the North-East (and sometimes they include Scotland!) but the people of Newcastle will easily distinguish between the speech of Northumberland, Sunderland and Durham. Local speakers are familiar with the accent and can more easily identify many linguistic features while those further away and less familiar may rely on fewer features, such as the short or the long A as in “bath” which is a feature generally distinguishing speakers north and south of a line drawn from The Wash to the Wirrell.

Isoglosses

The research underlying the notion of linguistic pools is the charting of isoglosses across the country. An isogloss is a line drawn between geographical points where a given language feature is identified. Like isobars charting similar areas of atmospheric pressure and contour lines showing areas of the same height, an isogloss shows areas where vocabulary, syntax or pronunciation features are similar and can therefore be used to draw lines showing differences.

In large separated language groups the accumulated differences lead to incomprehension so at some point it could be said that they are different languages (as vulgar Latin lead to a large number of Romance languages).

What can also happen under some influences, such as enforcement and state controlled standardisation (more so in the written form than in speech) is that there is uniformity – the pressure on idiolects to be similar instead of varying as they do naturally. These influences could be similar to the influences listed above (Time, Geography, Government, Social), but work to different effect. As conformity in a closed community brings public school pupils to speak in a similar way, state school pupils may emphasise their local dialects in order to differentiate and distance themselves. So tribal and social groups include themselves and exclude each other, in language as in behaviour. Their language is as important an identifier as their uniform or their sporting allegiance.

Influences

Examples of languages exhibiting unification and division. In nearly all cases several different influences are at work:

- French in France and Spanish in Spain – two languages in two countries adjacent but separated by mountains.

- Papua New Guinea – where there are said to be 850 languages in cultures divided by narrow valleys and insuperable mountains

- Government – Italian Unification (The Resurgence) which saw different states unified under one government and one language.

- Nationalism – the separate Greek and Turkish areas of Cyprus; Arabic and Hebrew speakers in the middle east; the Basque people in Spain; Welsh nationalism raising the profile of Welsh in an English speaking country.

- Migration – The USA and Australia adopted English as a common language though immigration was by many language speakers. In practice Melbourne Australia also has the second largest group of Greek speakers after Athens itself.

- Conquest - Norman French (and Latin) imposed on Anglo-Saxon speaking people by being used as the exclusive language of the court and the law; English used as a common language by the British Empire, notably in India.

- Religious and tribal – Hindi is now the official language of India, with English secondary. However the census of 1961 identified 1652 languages, of which the main ones are

Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Chhattisgarhi, Dogri, Garo, Gujarati, Standard Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Khasi, Kokborok, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Mizo, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit , Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu.

- Spanish in South America is directly related to the Spanish Conquistadors, while Portuguese exploration introduced the language which is now spoken in Brazil. Though Spanish and Portuguese have similar roots in Latin the influence of time (Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1139, the Conquistadors followed Columbus’ discovery of The New World in 1492) and distance mean that South American Spanish is seen as a dialect of the Spanish of Spain.

Conclusion

For all the variety that comes with linguistic change, there is an overwhelming (though not absolute) benefit for people with a common view and history to understand each other so originality will take a back seat to comprehensibility.

We may have our regional or personal linguistic quirks, but it pays to be understood.

|

|